About the Holiday

Today’s holiday is dedicated to the man—Leonardo of Pisa, today known as Fibonacci—who promoted awareness throughtout Europe of the number sequence that now bears his name. First appearing in Indian mathematics and linked to the golden triangle and the golden ratio, the number pattern states that each consecutive number in the series is the sum of the two preceding numbers: 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34…. This sequence is found again and again in nature in such arrangements as leaves on a flower stem, seeds in a sunflower, the tapering of a pinecone, the swirl of a seashell, and manys. These precise compositions allow each leaf to get enough sunlight, make room for the correct number of petals, or squeeze in as many seeds as possible. To celebrate, learn more about this sequence and then observe patterns in nature. A good place to start is with today’s book!

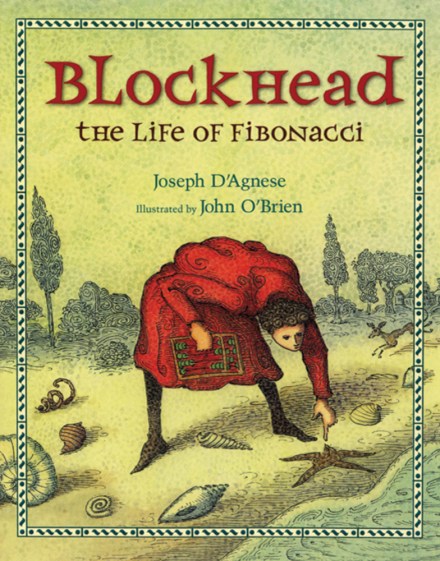

Blockhead: The Life of Fibonacci

Written by Joseph D’Agnese | Illustrated by John O’Brien

Leonardo Fibonacci introduces himself this way: “You can call be blockhead. Everyone else does.” He goes on to reveal that he acquired that nickname because he loved to think about numbers. Once when his teacher gave the class ten minutes to solve a math problem, he knew the answer in two seconds. At home he counted everything he saw. When he was bored his mind pondered the patterns he saw. For instance, on that school day while his classmates worked on the problem, Leonardo spent the time gazing out the window. H e noticed 12 birds sitting in a tree. How many eyes was that? How many legs? “And if each bird sang for two seconds, one bird after the other, how long would it take all of them to sing?” He was counting these answers in his head when his teacher yelled, “‘How dare you daydream in my class!’” He told Leonardo there would “‘be no thinking in this classroom—only working! You’re nothing but an absent-minded, lazy dreamer, you…you BLOCKHEAD!’”

Image copyright John O’Brien, courtesy of Henry Holt and Company

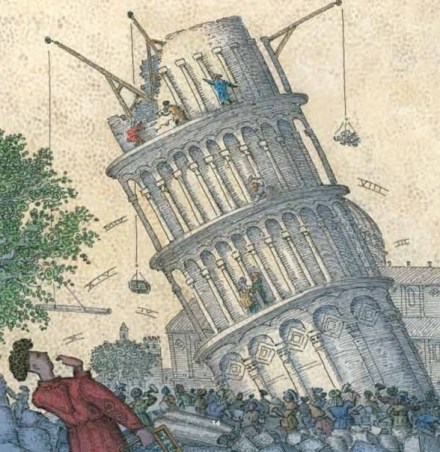

Leonardo ran from the room into the city he loved—Pisa, one of the greatest cities in 1178 Italy. A new tower was being constructed—although the builders were having trouble with their math and the tower stood at an angle. He was so enthralled with the math he saw all around him that he nearly walked into danger. “‘What are you, a blockhead?’” a woman shouted. Leonardo’s father was angry and embarrassed by his son’s reputation in town. He wanted Leonardo to become a merchant, and took him to northern Africa to learn the business.

Image copyright John O’Brien, courtesy of Henry Holt and Company

In Africa Leonardo learned a new number system. Instead of Roman numerals, the people used numbers “they had borrowed from the Hindu people of India.” In this system XVIII became the much easier 18. During the day Leonardo handled his father’s business accounts, but at night Alfredo, his father’s advisor and Leonardo’s champion, accompanied him as he learned the new number system. As Leonardo grew older, his father sent him on trips to other countries to conduct business. In each Leonardo learned new mathematics concepts. In Egypt he learned about fractions. In Turkey and Syria he discovered methods of measurement. In Greece he learned geometry, and in Sicily he used division and subtraction.

Image copyright John O’Brien, courtesy of Henry Holt and Company

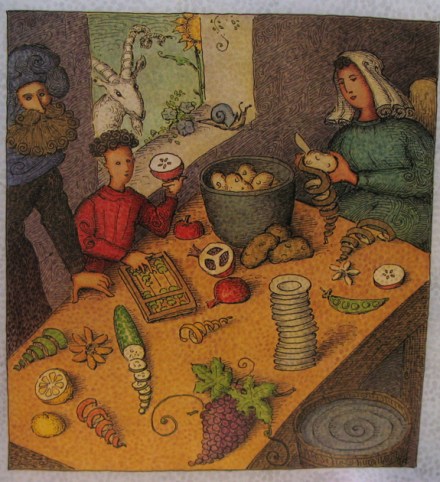

One day Leonardo “began to write a book about Hindu-Arabic numerals” and included riddles to demonstrate the ideas. One was about a pair of rabbits. Leonardo asked Alfredo to tell him how many baby rabbits would be born within one year if it took a baby one month to grow old enough to have babies of its own and one more month to have a pair of babies. Alfredo tried to solve it but couldn’t. As Leonardo explained the sequence of adult pairs and baby pairs of rabbits to Alfredo, he noticed a pattern. At the end of month two, there would be 1 grown-up pair of rabbits and 1 baby pair; at the end of month three there would be 2 grown-up pairs and 1 baby pair; at the end of month 4 there would be 3 grown-up pairs and 2 baby pairs…. Leonardo saw that by adding “any two consecutive numbers in the pattern,” you’d get the next correct number. This discovery made solving the problem even easier.

Image copyright John O’Brien, courtesy of Henry Holt and Company

Leonardo’s work with math soon spread across Europe. Frederick II, the ruler of the Holy Roman Empire invited Leonardo to visit. There Frederick’s wise men challenged him with math problems that were no match for Leonardo’s quick brain. Frederick II didn’t call Leonardo a blockhead, instead he said he was “‘one smart cookie.’” When Leonardo went home, however, the people of Pisa grumbled and complained. They thought the old Roman numerals were good enough.

Leonardo set out to prove how valuable Hindu-Arabic numerals were. He began observing nature, and everywhere, from the petals of a flower to the arms of a starfish to the seeds in an apple, Leonardo discovered the same numbers—the sequence he had discovered in the rabbit riddle. He realized that these numbers could be used in different ways—to draw a spiral; the same type of spiral found within pinecones and the center of a sunflower.

Image copyright John O’Brien, courtesy of Henry Holt and Company

Leonardo finishes his story by relating that even though he is now old, numbers still delight him, as does the secret Mother Nature cleverly uses to organize the world and even the universe. He invites readers to look again through his story and find the places where his Fibonacci sequence appears.

More biographical information about Leonardo of Pisa plus a discussion of where readers can find Fibonacci number patterns in nature and a scavenger hunt through the book follow the text.

Blockhead: The Life of Fibonacci is an engaging, accessible biography that describes this mathematical scholar’s life and theory in a clear and entertaining way, whether their thing is math and science or English, history, and art. Joseph D’Agnese immediately entices kids into the story with the revelation of how Leonardo acquired the nickname that gives the book its title. Using anecdotes such as the birds in the trees and the rabbit riddle, he invites readers to think like Fibonacci, leading to a better understanding and enjoyment of his life story and the mathematical concept. The idea of using your talents and passions wherever you are—as Leonardo does in his work for his father—is a valuable lesson on its own.

John O’Brien’s wonderfully detailed illustrations take children back to early Italy and the Mediterranean with his depictions of Leonardo’s school and town, as well as the under-construction Tower of Pisa and the influential cultures of other countries he visited. Cleverly inserted into each page are examples of the Fibonacci sequence at work—in whorls of wood grain, the spirals of women’s hats, the web of a spider and horns on a passing goat, and so many more. The rabbit riddle is neatly portrayed for a visual representation of the math involved, and the way nature uses the pattern is also organically portrayed. Children will love searching for and counting the various ways Fibonacci’s seuqence is used throughout the illustrations.

Blockhead: The Life of Fibonacci is a fantastic book to share with all children, especially as they begin to learn mathematical problem solving, the value of math, how it is used, and how it occurs naturally in the world. The book makes a marvelous teaching resource and addition to classroom libraries and also a great addition to home bookshelves.

Ages 5 – 9

Henry Holt and Company, 2010 | ISBN 978-0805063059

To discover more books by Joseph D’Agnese for children and adults visit his website!

Find a vast portfolio of cartoon and illustration work by John O’Brien for kids and adults on his website!

Watch the Blockhead: The Life of Fibonacci book trailer!

Fibonacci Day Activity

Spiral Coloring Page

Have fun coloring this printable Spiral Coloring Page that is inspired by Leonardo Fibonacci’s work.

Picture Book Review